Any company that wants to be successful in the long term must keep up with the times and invest in development and innovation. More and more companies are therefore betting on start-ups and directly investing in them. But such an investment is not an acquisition like any other. You have to prepare for it both professionally and managerially.

The pace of change has never been this fast, yet it will never be this slow again. Those are the words of the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2018, eloquently describing the speed of progress, not just in technology. To keep up with this pace, the world's technology giants need to stay ahead of the curve. Many of them, such as Intel Corporation, SAP or Microsoft, have therefore long been procuring innovation through investments in start-ups.

These strategic investors, or corporate venture capital (CVC), are usually a division or separate subsidiary of a large operating company that invests its own funds in a start-up operating in the same or a related industry. For example, a large technology company can benefit from investing in and partnering with a start-up using artificial intelligence (AI). Such a relationship is mutually beneficial. The investor brings to the start-up not only funds with the prospect of a decent return, but also specific know-how in his field and business development, including a wide network of contacts and clients.

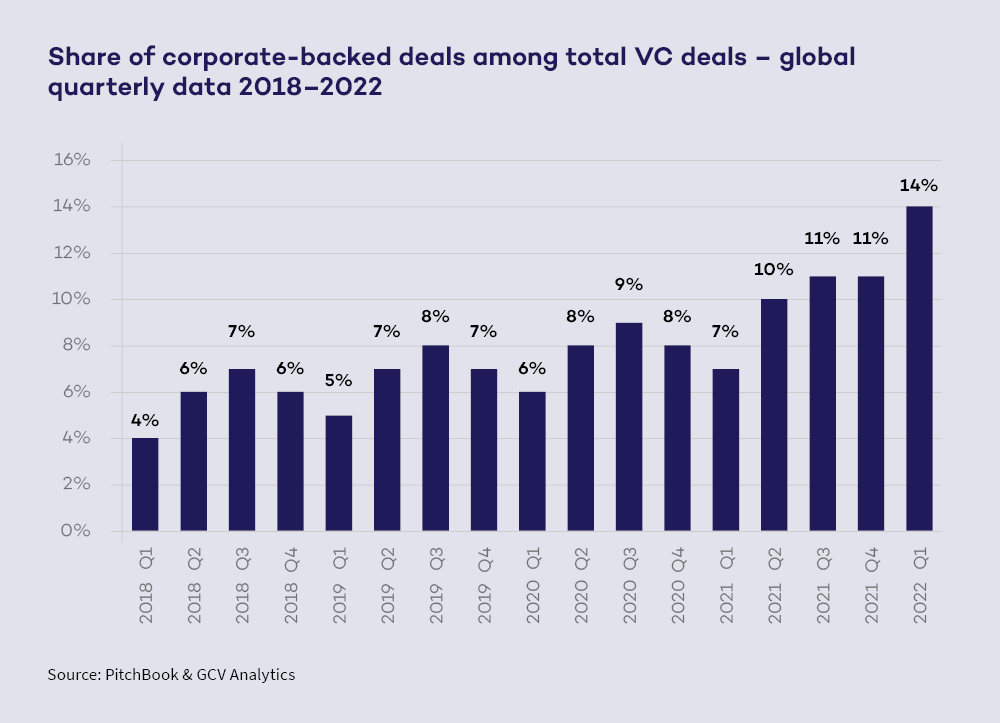

Following the example of large technology companies, more and more companies have been interested in venture capital investments in recent years. Corporate venture capital is growing dynamically and the share of corporate investments in the overall venture capital market is increasing. Over the past five years, it has increased from 5–6% to well over 10%, according to the Global Corporate Venturing platform. In the first quarter of 2022, CVC recorded more than 1,500 deals with a total estimated value of USD 69.6 billion. Corporate venture capital investments thus accounted for 14% of all venture capital deals.

And why do companies do this? For corporations, the reason for investing in venture capital is not just financial gain. They can also achieve other strategic objectives. In particular, access to innovations.

You can't stop progress

Innovation means "renewal", "improvement" or "streamlining", which is exactly what any company that wants to be successful in the long term should constantly strive for. The practice of investing in start-ups is also increasingly being emulated by players in non-technical fields. For corporations, such investments have two crucial dimensions.

The first one is aimed at technological improvements that companies do not have at the time, and which take time and money to develop. If a start-up offers an improvement on the market, it makes sense to buy such an innovation and thus eliminate the risk associated with unsuccessful development, not to mention the reputational damage that may result if the company’s own technological development fails.

For companies, investing in start-ups is investing in innovations and promising people with the potential to create or acquire something that will advance their businesses.

The second and equally important aspect of such investments is the ability to bring into the company the ideas, work and results of people who would not otherwise be willing to work for such a company. In this sense, investments in start-ups are primarily investments in promising people with the potential to create or acquire something that will advance the corporation’s business itself.

While the trend of large companies investing in start-ups is growing abroad, there is still a certain caution in the local market. This is mainly due to a lack of experience with the investment process and its specifics. This limits the ability of the corporation to select the right founders and, more broadly, to realistically evaluate the investment opportunity.

Technology start-ups in particular can be quite an expensive "business", often with uncertain results from a corporate perspective. Hence firms’ lower risk appetite. Concerns that the investment in the start-up will not work out cause the management to fear that it will burn the corporation’s money with a failed investment.

Concerns can be allayed by careful preparation of the investment itself, which will reveal potential risks. It is therefore essential to understand how the investment process works and to better understand its specifics. Investing in a start-up is not an acquisition like any other, and therefore it is necessary to prepare for it both professionally and managerially.

Caution is in order

From the very beginning when considering an investment, it is necessary to think about protecting the value of the company being acquired and setting up the right investment structure. If you are acquiring a new company, it is important to conduct legal, financial and other (e.g., cyber security or technology) due diligence. However, this applies tenfold to investing in a start-up; not so much because the legal situation of start-ups is so wild, but primarily so that you as managers are aware of all the potential risks. That way you will also have realistic expectations from the beginning.

When setting up a post-investment structure, in addition to the classic issues related to taxes or regulation, the governance of the start-up must also be carefully considered. For many reasons, it is not advisable to quickly integrate start-ups into the existing corporate structure. It is therefore necessary to agree who will be responsible for what and how the start-up’s management will check on the implementation of the business plan.

Corporations like to solve this by nominating a person to the statutory body and setting up a supervisory board, which they control with their representatives. Although such a supervisory board is often unnecessary and bureaucratizes the start-up's activities, it gives corporations a sense of greater security.

However, potential concerns on the investor's side can also be avoided by preparing a detailed business plan. If prepared realistically and approved by you as an investor and the founders, it works as an ideal tool for evaluating the success of a start-up's business management. It provides a basis for investment decision-making in terms of expected return on investment and provides a structured outline for the company's activities for the next period.

Remember, however, that start-ups’ business plans cannot be carved in stone, and that flexibility is the key to start-up success. Especially in today's dynamic times, it can easily turn out that the original business plan does not work and the project comes to a dead end. But that does not immediately mean it cannot get out of it. In such situations, pivoting, i.e. a change of direction, a change of strategy, can work well to steer the investment back in the right direction. This is often where the experience of the corporation plays a key role, as it can help move the start-up's business forward.

Keeping ideas safe

Pay special attention to intellectual property (IP) and technology protection. Start-ups are not ironworks – their value lies not in their gross production power, but in the intellect of their people. Ideas and innovations must therefore be protected in one of the (inter)national public databases, which then makes the protection of these rights enforceable in court. These include patents, utility models, trademarks, domains, but in a broader sense also the often neglected (and of course unregistered) NDAs, i.e., non-disclosure agreements, and also licensing agreements.

If you are investing in a start-up, ask your lawyer for a description of how intellectual rights are protected and how the different levels of protection interact as part of the due diligence process. Remember that everything starts from the bottom, i.e., from the employees and other collaborators who create the IP. If you have not concluded the right contracts with them, then the start-up does not own the IP and its value is marginally close to zero.

The involvement of IT technology experts is also recommended, as it happens from time to time that an innovative IT solution, in which the value is supposed to lie, is not so innovative. In addition, these experts can help with research on future expansion and scaling, integration and synergy opportunities, as well as monitoring potential IP infringements, which will be very useful for you as an investor, not only when considering the amount of investment.

Contracts as a basis

Investing in a start-up is primarily a legal construct. As a result, such investment always requires specific legal documentation, which varies according to the maturity of the start-up. The quality and sophistication of contractual documentation prevents conflicts between investors and founders, and has a direct impact on the value of the start-up.

In general, it is rare for a corporation to buy 100%, and, in the vast majority of cases, partnerships are formed with start-up founders. Moreover, corporations usually do not invest in early investment rounds (seed), but are rather interested in start-ups that can already prove that their business model works.

A typical contract for the early stages of a start-up is called a convertible loan – the investor can choose between a stake in the start-up and a return of the investment after a certain period of time. In most cases, however, when a corporation invests, a share purchase agreement (SPA) or an investment agreement (IA) will be concluded for the purchase of shares and a shareholders' agreement (SHA) will be concluded to regulate the relationship between the investor and the founders.

A good agreement between the investor and the founders should keep in mind the management of the start-up – it should define who will run it managerially, who will control it, and under what conditions the founders may be replaced with professional managers or removed if problems arise.

The SHA should also address further funding of the start-up. It is necessary to think about what will happen when the start-up runs out of money from the investment and who will bear the costs of further operation and development. In a standard venture capital investment, this is usually addressed in the next round of funding, when the basic question is whether the corporation wants other investors.

The agreement should also describe the procedure for the possible exit of the founder. For these cases, the SHA uses English terms such as ROFO/ROFR, which are forms of pre-emption right; drag along, i.e., the right of the majority shareholder to force the minority shareholders to sell; tag along, i.e. the right of the minority shareholder to force the majority shareholder to sell; vesting, etc.

Last but not least, the agreement should also include methods to resolve disputes between the shareholders and the procedure for preventing them so that the start-up is not paralysed.

Motivation as the basis for success

If you want your start-up to work under the wings of a corporation and continue to grow dynamically, keep in mind that a motivated founder is a committed founder. It is therefore the founder who will have the greatest interest in the continued prosperity of the start-up. So do not forget to motivate key people and start-up employees.

In standard acquisitions, the buyer sooner or later changes the management and then ideally just waits for the dividend. However, this is completely at odds with the reality of start-ups, where it is true that extreme performance by key people must be highly rewarded. So turning a start-up into a small corporation and including the founders and key people in standard corporate incentive schemes is not the best approach.

In the context of incentive schemes, it is therefore always necessary to think about who the right employees are and how to set the reward. In addition to the commercial issues, it is also essential to choose the right legal form of incentive scheme, as this has major tax implications.

The current Czech law does not yet offer optimal solutions. Given the hostility of tax regulation in the area of employee stock ownership plans (so-called ESOPs), there is a need to devise alternative corporate structures that preserve a maximum of the incentive component. Creating functional and tax-efficient incentive schemes is thus the reason that leads to the creation of foreign holding structures.