A simple, fast, and digital building procedure – this is what the new building acts on both sides of the Czech-Slovak border promise today. How are they similar and how do they differ? The fiction of consent, black buildings, digitalisation, the decision makers – check with us for how to build in Slovakia and the Czech Republic according to the new building regulations.

In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the building permit procedures that take months or even years, loads of paperwork and an endless quest for opinions should by now be a thing of the past. The new Building Act came into effect for most buildings in the Czech Republic in July 2024. In Slovakia, the new Building Act came into effect nine months later – on 1 April 2025. Whether you are involved in property development, real estate, industry or if you simply need to expand your corporate headquarters, these changes will affect you. Let us take a closer look at what the new acts in both countries have in common, and where they diverge.

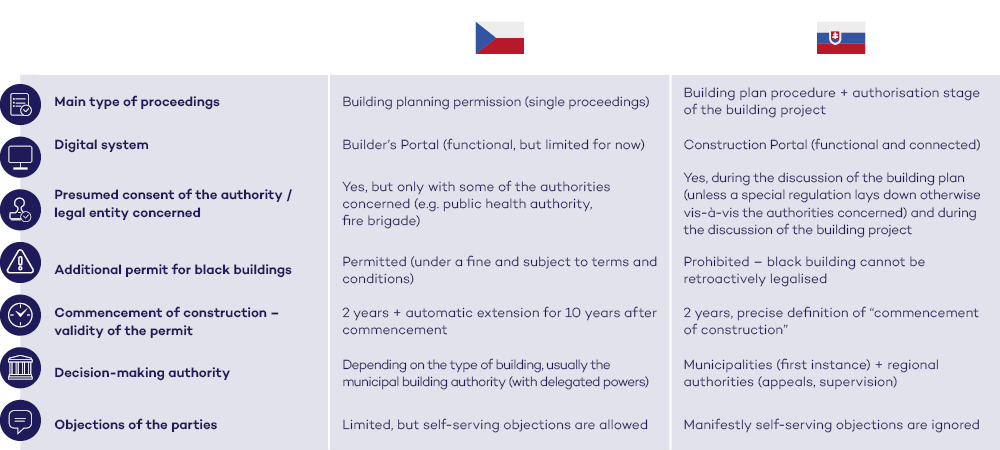

The permitting process has been greatly simplified in both countries. The dual process of planning decision and building permit in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia has been replaced by a single procedure.

The permitting process has been greatly simplified in both countries. The dual process of planning permission and building permit in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia has been replaced by a single procedure. In the Czech Republic, this is called a building planning permission, in Slovakia it is called a building plan procedure. But the result is the same in both countries: one procedure, one decision, less paperwork and less waiting time.

The difference, however, is that if you want to build in Slovakia, you must initiate a discussion on the building plan before starting the procedure. This means that you or your designer will upload the project documentation into the electronic information system and request that the authorities and legal entities concerned issue binding opinions or statements on your building plan.

Once you have collected all the binding opinions, you (or your designer) will prepare a report on the discussion of the building plan. This report should evaluate the comments on the opinions and statements, i.e. indicate who specifically made each comment and how the comment was evaluated, if applicable.

Subsequently, as part of the building plan procedure, you will submit a report on the discussion of the building plan to the building authority together with the plan itself. Once a decision on the building plan has been issued, you will ask the building authority to authorise the building project. If the building authority approves the building project, it will issue an authorisation clause and you can start building in Slovakia.

The Czech Act, on the other hand, does not specifically regulate the discussion of the building plan or the building plan procedure. In the Czech Republic, you can voluntarily obtain binding opinions and other supporting documents before proceedings are initiated. Such steps, however, are not specifically laid down in procedural law. Nonetheless, this will speed up the entire permitting process and prevent any complications and delays.

According to the new Building Act, however, you can also leave it entirely to the building authority to obtain opinions. The authority is obliged to request them from the authorities concerned itself. Even if you provide only part of the statement and some opinions are missing when you submit the application, the authority cannot consider this as a defect. In practice, however, such a procedure is not yet used, especially for larger buildings. Building authorities are already overloaded; moreover, it is quicker to arrange the opinions yourself.

Simply online

There were high expectations in both countries for the digitalisation of building procedures. In the Czech Republic, building permits can be applied for electronically via the Builder’s Portal, which has not functioned perfectly since its introduction last year. This year, Slovakia launched the Construction Portal. This digital space collects all necessary documents, permits and submissions in electronic form. At the same time, the portal facilitates communication between all construction participants.

Users can, among other things, upload and manage building documentation electronically, submit electronic applications and monitor the status of the permitting procedure, and obtain binding opinions and statements from the authorities concerned. They can also verify and manage construction information.

The future direction is therefore clear in both countries: complete digital building permit procedures are set to become the industry standard. Currently, most things can already be done online. Although there were certain technical problems in the Czech Republic in the early days (which still persist in some areas), digital solutions are already in use and just need fine-tuning to everyone’s satisfaction.

Silence means consent

Presumed consent should also help to speed up the granting of building permits. InSlovakia, the authorities, bodies or legal entities concerned are obliged toissue a binding opinion or, in the case of legal entities, a binding statementwithin 30 days of receiving the application or, in the case of complexbuildings, within 60 days. If they fail to do so within these time limits, theyare deemed to have no comments or requirements regarding the content of thebuilding plan, or its incorporation into the building project (with exceptionsfor the authorities concerned, where a special legal regulation providesotherwise). Presumed consent also applies if the authority or legal entityconcerned fails to issue a compliance clause within the statutory time limitwhen discussing the building project.

Presumed consent is laid down in the new Czech Building Act in a manner similar to the previous regulation. If the authority concerned fails to issue a binding opinion within 30 days (or 60 days in exceptional cases), it is deemed to have given its consent. This presumption, however, does not apply absolutely. In Czech building law, presumed consent is possible with the public health authority, the fire department or the road administration authority, for example. It is not applicable to opinions in the field of nature protection, where specific acts explicitly exclude it.

Where to apply

In Slovakia and the Czech Republic, the acts do not differ much in terms of where you actually apply for a permit. In Slovakia, municipalities continue to act and decide as building authorities in the first instance, exercising their delegated state administrative powers. What is new, however, is that there are now eight regional offices for spatial planning and construction in Slovakia, responsible for deciding on appeals against municipal building authority decisions. They also inspect building authorities and handle complaints filed against them.

Furthermore, a new central state administration body called the Office for Spatial Planning and Construction has been established in Slovakia. It has national competence for construction, expropriation and spatial planning (except for environmental aspects).

Institutional reform has also been a major topic of discussion in the Czech Republic. The new Czech Building Act originally envisaged a unified system of state building administration, which was to consist of the Supreme Building Office, specialised and appellate building offices and regional building offices with territorial offices in 205 municipalities with extended jurisdiction. However, before the new Czech Building Act came into force, it was fundamentally changed by an amendment in 2023. This amendment returned building authorities back to municipal and regional authorities with delegated powers, and binding opinions back to the authorities concerned. The only remaining part of the original state building administration structure is the specialised Transport and Energy Building Office. This office now makes first instance decisions on the most significant (so-called reserved) constructions, such as motorways, railways or power plants. According to the latest amendments to the building regulations, it now has sole decision-making power over larger renewable energy plants (i.e. appeals are inadmissible).

Construction commenced

According to the new Slovak Building Act, you must start construction work within two years, otherwise the authorisation clause (formerly the building permit) becomes invalid. In practice, doubts have started to arise in Slovakia as to whether the commencement of construction also encompasses the mere carrying out a few initial preparatory works. The new act clarifies this issue, stating that the start of work is no longer specifically considered to be the fencing of the building site and the establishment of the building site, equipping the building site with the necessary facilities, providing access for people and vehicles to the building site, or water and electricity supply, or removing vegetation from the building site, carrying out initial soil clearing, removing waste from the building site or just marking out the construction area. By contrast, the commencement of construction is defined as “the start of construction work directly related to the execution of the construction”. These are, for example, earthwork, demolition, assembly or craft work required for the execution or alteration of the building, construction adaptations and maintenance or removal of a building.

According to Czech legislation, building planning permission is also valid for two years from the date of its entry into force. In addition, the new Czech Building Act lays down a new rule that if you start construction during the permit’s validity period, its validity is automatically extended to 10 years. This is an incentive to complete buildings that would otherwise become illegal after 10 years. Unlike the Slovak legislation, however, the Czech Act does not define the moment of commencement of the plan, which therefore remains a matter of interpretation and proof in practice.

Black buildings

In Slovakia, too, they want to radically address black buildings constructed without permits. From April 2025, any building to which the new regulations already apply that is constructed through unauthorised construction work (without an authorised building project or in violation of it) will not be able to be legalised in any way. If the authorities discover unauthorised construction work carried out without an authorised building project when the project is inspected, the building inspector will instruct the builder and the contractor to stop immediately. If the unauthorised construction continues, the building inspector will notify the building inspectorate. The inspector will then order the owner of the building to remove the building, the construction adaptations and modifications made through unauthorised construction work.

A similar tightening measure was also considered in the Czech Republic, where the original version of the act required the builder to demonstrate good faith in order to obtain an additional permit. However, the 2023 amendment has relaxed this requirement and an additional permit for illegal construction is still possible in the Czech Republic if the builder pays a fine for the offence and if the construction complies with building regulations and does not require an exemption. This change was based on the assumption that it would be pointless to demolish a black building that otherwise complies with all legal regulations, and then rebuild it again once it has been permitted.

Objections are inadmissible

In Slovakia, there has long been a problem with speculative entities that often entered into proceedings with the intention of causing harm and prolonging them artificially. According to the new Building Act, however, Slovak building authorities should no longer consider proposals, comments and objections from parties to proceedings that do not pursue the protection of their rights and legally protected interests. This means that they will disregard objections that are intended to cause harm, gain an unfair advantage or delay or obstruct proceedings.

Unlike the Slovak Act, the Czech Act does not prohibit objections to the same extent, but to a certain extent it does guarantee that building authorities will not consider manifestly unfounded objections.

Different kinds of buildings

One of the less obvious, yet in practice crucial differences is the definition of a building itself. While in the Czech legislation, a building does not require a fixed connection to the ground and the key parameter remains the purpose of the building, i.e. whether it is intended for permanent use, production or housing, the Slovak regulation focuses more on the building’s physical characteristics and the main role is played by the fixed connection to the ground: “A building is a structure erected by construction work that is firmly attached to the ground or whose positioning requires the treatment of the subgrade.”

Therefore, a mobile home can easily be considered a building in the Czech Republic, while in Slovakia the same object may not, thus escaping the entire permitting regime. In both countries, therefore, more attention needs to be paid not only to documentation but also the interpretation of the acts.

The new Slovak Building Act has also expanded the definition of small buildings. It is no longer just an accessory building to the main building; rather, it is any building that cannot significantly affect its surroundings. The Act lays down a non-exhaustive list of examples of small buildings, which have a built-up area and height of no more than 50 m2 and 5 m2, respectively. Examples of small buildings include power-generating, heating and cooling installations from renewable sources with a total installed capacity of up to 100 kW inclusive. This includes charging stations for electric vehicles with a total capacity of up to 22 kW with one or more outdoor charging points, or the electrical equipment for the charging stations and their installation.

The situation in the Czech Republic is similar. Annex 1 of the new Building Act sets out a very detailed list of small buildings. It also extended the range of small buildings that can be built without permission or notification of the building authority.

Both acts in the Czech Republic and Slovakia also introduce a category of reserved buildings. These are technically complicated structures that can only be carried out by certified contractors in order to improve the safety and quality of construction. In the Czech Republic, they are permitted by the state Transport and Energy Building Authority and are subject to some additional requirements concerning their design, construction and supervision.

In our comparison, the Czech and Slovakbuilding acts therefore aim at the same goal: faster and more efficientproceedings. However, each country has chosen a slightly different approach.For entrepreneurs and developers, this means thinking strategically andaddressing the differences in the preparatory stage. Their detailed knowledgecan be the key to successfully implementing your building project.