In March this year, the Czech government made history by using its powers under the Foreign Investment Screening Act (the FDI Act) for the very first time to block a foreign company's investment. What key takeaways are there from this? And if you’re working with a foreign investor, could this put your company at risk?

Foreign investment rules in the Czech Republic have been developing quietly until now, but they've just taken their first concrete form. What is FDI and why should you care?

Foreign investment, whether it's buying a company, taking a minority stake, or starting a greenfield project, is a key driver of economic development. But on the other hand, it can also bring security risks, especially if investors from countries with different strategic interests get involved in sensitive areas. Screening foreign investments helps eliminate potential risks. It lets the state control these investments, assess how risky they are, and potentially block them.

The law distinguishes two kinds of investments: those that need mandatory notification, and those the Ministry of Industry and Trade can examine on its own.

The Czech Foreign Investment Screening Act came into force on 1 May 2021. The Act aims to protect the security and public order of the Czech Republic by enabling the examination of foreign investments from outside the EU. Under the Act, a foreign investor is defined as any entity (including natural persons) which has its registered office or nationality outside the EU or which is controlled by such a person.

This legislation is primarily directed at investors from countries deemed sensitive, such as China, Russia, and Iran. However, investors from the USA, the United Kingdom, Norway, Switzerland, and Israel are also required to apply for investment permits in the Czech Republic.

The law distinguishes two kinds of investments: those that need mandatory notification, and those the Ministry of Industry and Trade can examine on its own. This dual mechanism is uncommon in Europe, being present in only three other countries, including Slovakia.

Specifically, the notification obligation applies to investments concerning critical infrastructure elements, the arms industry, or the production and development of dual-use goods. These products, while commonly employed in civilian applications, are also adaptable for military purposes or, due to their inherent properties, may be diverted to the production of weapons of mass destruction (or their delivery systems). Their scope encompasses a wide range of items, including drones, cybersecurity and cryptography software, and various chemical substances.

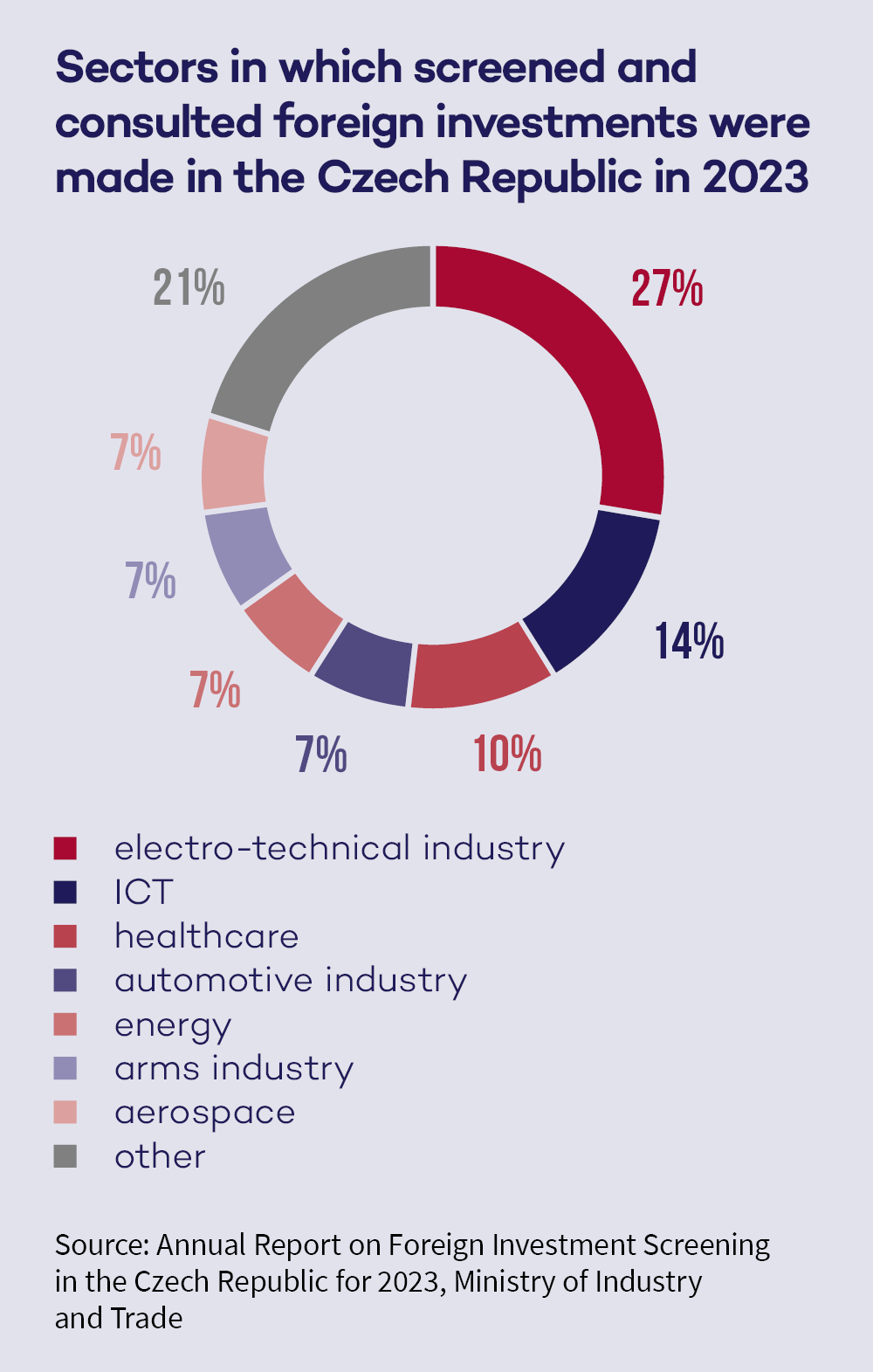

In 2023, the Ministry primarily reviewed investments in the electrical industry, information and communication technologies, and the health sector. Its scope also encompassed investments within the arms, aerospace, and automotive industries, alongside those in the financial, transport, services, and construction sectors.

In the context of other investments with potential implications for national security and public order, investors may also voluntarily provide notice of the transaction to obtain legal certainty regarding its compliance. Failure to do so, however, carries the risk that the investment could be subject to proactive review by the authorities for up to 5 years after its completion.

First ban in history: the Emposat case

In March 2025, the Czech government issued a classified resolution, empowering the Ministry of Industry and Trade to prohibit the Chinese company Emposat from proceeding with its planned investment in the country. Emposat’s proposal involved operating a satellite earth station in Vlkoš, a village located in South Moravia. Despite being a greenfield investment, the government determined that the project posed a potential threat to Czech national security or public order. Sources indicate that intelligence played a significant role in this decision.

The Brno-based company Pekasat was designated as Emposat's partner in the Czech Republic. Pekasat, however, asserts that its involvement was limited to an infrastructure lease, and that it had no financial or operational connection with the investor. Nevertheless, the project was halted. The key lesson here is: even an inconspicuous project not subject to mandatory notification can be subsequently stopped by authorities should it later be deemed hazardous.

Active market monitoring

Despite this being the first prohibition since the law’s enactment, it does not indicate that the FDI regime has been ineffective. The Ministry has previously stated it has received numerous notifications and conducted multiple reviews since 2021, with the majority of cases concluding without adverse findings. Consequently, the market is under rigorous oversight, with even greenfield investments drawing state interest. Furthermore, our information corroborates that many reviews of foreign investments are not initiated based on investor proposals, but rather through the authorities’ own proactive monitoring, specifically at the behest of the Ministry of Industry and Trade.

We reiterate that the Act empowers the Ministry to initiate a review with a retroactive scope of up to five years. As a result, no investment, even one undertaken without prior notification, can be considered entirely secure. It is important to consider the potential changes in political representation and state security policy that may arise from current geopolitical developments, not only in the Czech Republic but also across Europe and globally, within the next five years.

Moreover, international experience indicates a progressive tightening of FDI legislation and an increase in the scope of prohibited investments. Furthermore, these statistics fail to capture instances where a foreign investor abandons the pursuit of an investment following protracted negotiations with the regulatory authority.

Wider EU practice — The Czech Republic is not alone

The Czech Republic's approach to foreign investment screening is consistent with that of many other European Union members. Twenty-three EU countries, including Germany, France, and Italy, currently operate such screening mechanisms.

The Czech regulatory regime is notably more stringent than those of other nations, impacting not only the acquisition of existing enterprises but also new investments, and conferring extensive powers upon the Ministry of Industry and Trade. The government provides no detailed rationale for its decisions, and the Ministry’s annual reports are consistently brief, general, and frequently issued several months late. This all significantly hinders investors’ ability to accurately assess genuine risks.

What constitutes a safety risk?

How should foreign partners investing in your company be evaluated for their potential to pose risks to national security? The terms ‘security’ and ‘public order’ lack precise legal definition, which grants considerable latitude for interpretation regarding what constitutes a specific disruption. In practice, their application is frequently guided by the recommendations issued by the European Commission. According to the European Commission, clear warning signs for foreign investment are identified through several key factors. These include concerns regarding access to sensitive data or technology, an investor’s links to government or military structures, the potential impact of the investment on critical infrastructure operations, or its effect on the availability of goods and services vital for security.

Non-public information, often derived from intelligence services, may also influence the decision to impose a ban. Nonetheless, unlike the public decisions issued by competition authorities and in relation to merger clearances, investment review decisions remain confidential. This stems from the sensitivity of the topics under review, yet it simultaneously implies that the entire vetting process lacks complete predictability for businesses.

Avoiding complications

The Emposat case consequently demonstrates that the FDI is an active instrument of state policy. What key considerations should foreign investors and other interested parties bear in mind? Seven crucial lessons can be gleaned from the initial ban and the ongoing monitoring of foreign investment:

1. Identify sectors at risk

Foreign investment into companies operating within the telecommunications, defence, information technology (IT), energy, or healthcare sectors is subject to a higher likelihood of regulatory intervention. This also extends to other critical technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and cybersecurity.

2. Consider voluntary notification

Even where reporting an investment to the authorities is not legally mandated, voluntary disclosure is permissible. It is particularly advantageous for complex transactions, especially those with intricate structures, or when the investor originates from a jurisdiction deemed high-risk. Voluntary notification provides enhanced legal certainty and significantly reduces the long-term risk of review by the authorities. Additionally, it offers a considerably less administratively burden some process compared to situations where the Ministry of Industry and Trade initiates an investment review proactively.

3. Make early contact with the Ministry

It is advisable to initiate informal communication with the Ministry at the earliest opportunity, ideally during the contemplation or negotiation stages of the investment. Our experience indicates that officials from the Ministry of Industry and Trade are receptive to dialogue. The authority values transparency and a cooperative approach from investors.

4. Anticipate post-investment scrutiny

Stipulate FDI risk clauses within the transaction documentation. Particular attention should be given to the inclusion of conditions precedent for compliance and cooperation obligations, especially when these pertain to regulatory compliance. This protection is equally applicable to target Czech companies. Should a foreign investor decline to consult with the Czech Ministry of Industry and Trade, and the investment subsequently be banned or made subject to modified conditions, the seller’s interests may be adversely affected.

5. Don't underestimate FDI risks

The risk of FDI review affects both the foreign investor and the Czech target company. It is therefore in their mutual interest to ensure the Ministry of Industry and Trade is notified and the investment approved prior to its implementation. The law further stipulates that an investment is also deemed to occur when the investor acquires as little as 10% of the voting rights or obtains access to sensitive information, systems, or technologies critical to the security of the state. Consequently, officials are empowered to initiate a review even for transactions that may not overtly resemble traditional acquisitions. It is therefore advisable to incorporate an FDI assessment for the target company into the transaction preparation. Should any uncertainty arise, it is prudent to initiate consultation with the Ministry and to secure contractual protection against potential intervention by the authorities.

6. Consult lawyers

Regulatory experience is essential for effective communication with authorities, strategic risk analysis, and the proper submission of notifications. An expert legal team is invaluable in this regard, providing assistance not only with formal requirements but also with crafting the strategy for engagement with the Ministry, which is often crucial for the transaction’s overall success.

7. Stay abreast of changes in legislation and interpretative practice

It is important to regularly monitor new cases, changes in the law, and the MIT's annual reports. European and Czech practice demonstrates an increasingly stringent trend, which is evident in the interpretation of sensitive domains and the authorities’ growing readiness to adopt more robust measures.